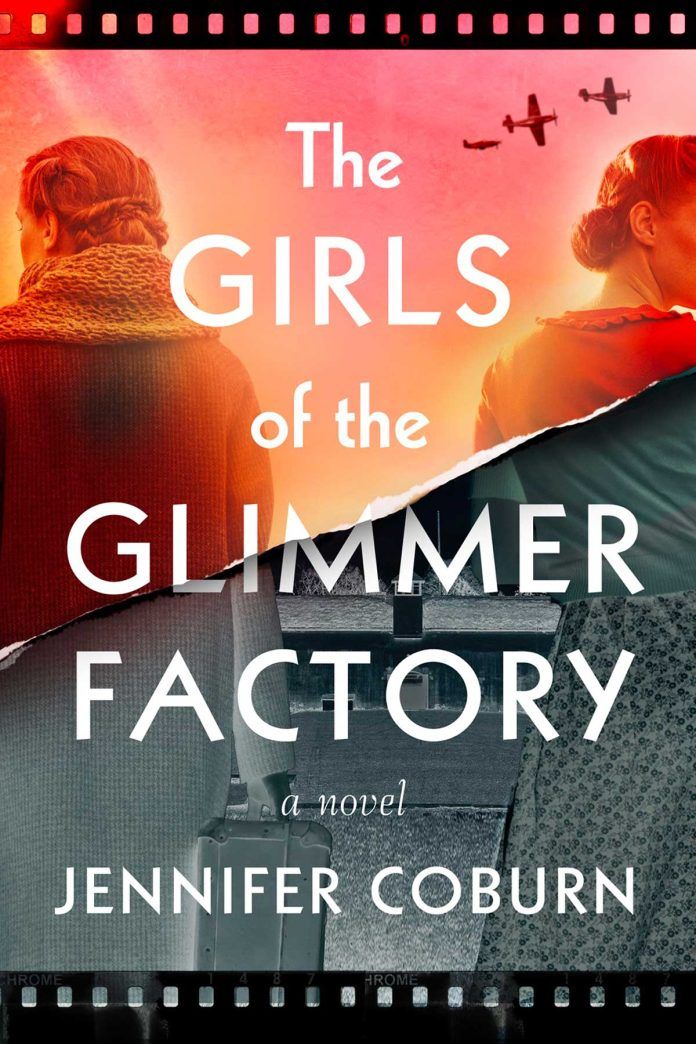

Jennifer Coburn’s new novel “The Girls of the Glimmer Factory” is now on presale, coming out on Jan. 28, one day after International Holocaust Remembrance Day. This follows her critically acclaimed debut of “Cradles of the Reich,” praised by the Associated Press as “setting a high bar for historical fiction.”

Tova Friedman, author of “Daughter of Auschwitz” said the novel is “A haunting page-turner of a story about friendship, bravery, and resistance, ‘The Girls of the Glimmer Factory’ brilliantly illustrates the need to combat propaganda as it threatens to gloss over evils. Written in shimmering prose, this deeply researched, must-read historical novel is acutely relevant to our present day.”

Coburn said the novel is a story about two childhood friends who meet again as adults at the Theresienstadt ghetto, a concentration camp the Nazis set up for propaganda purposes.

“It is set at Theresienstadt, but it is really about relationships and how the connections we forge can connect us to become the people that we were always meant to be, and discover who we really are at the core,” she said. “When the Nazis were codifying the Final Solution, the genocide of European Jews, they knew if they were going to perpetrate this mass crime, they were going to get questions from the global community. So, they said when the Red Cross demands to inspect, and when other humanitarian aid organizations start questioning us about death camps and gas chambers, we need to be ready with a place that we can take them that looks like a paradise settlement, where Jews have been relocated and are living in comfort to wait out the war.”

Coburn said Theresienstadt was really a workcamp, and a waystation to death camps in the east, about 60 miles north of Prague, and 60 miles south of Dresden.

“In the course of its three-and-a-half-year history 155,000 people passed through Theresienstadt. Some were there a few days, and some were there the entire time. The camp itself is a three- and one-half mile ghetto created by taking over Terezín, which was a Czechoslovakian military base. It was also the site of a propaganda film called “Hitler Gives a City to the Jews.”

Coburn said what she found fascinating about Theresienstadt was that an entire camp was built to deceive the entire global community.

“What happened there was somewhat miraculous,” she said. “A vibrant cultural community sprung to life by the prisoners. When many people hear about Theresienstadt, they think that the Nazis made an arts camp. But they did not. Prague was like New York City and Paris. So, if you were to going to say that in New York City that we are going to round up all the Jewish people, the gay people, and political dissidents, you are going to get a pretty creative and artistic group of people. That is what happened. Every day at Theresienstadt there were a variety of activities people could participate in after completing their 12 hours of slave labor, after they ate their meager rations, and before they went to their barracks and lived in squalor. There was a professional symphony, there were operas performed there, and some were composed there. This was not an ad-hoc group that put-on plays.

This was high level, highly renowned artists, like [Czechoslovak composer, pianist, and conductor] Rafael Schächter. Verdi Requiem was performed 16 times there, including a performance for the Red Cross inspection.”

Along with her extensive research in reading books, academic articles, prisoner diaries, interviewing experts, and watching films about Theresienstadt, looking at the massive collection of artworks created there, listening to the music performed there, Coburn said that she realized that she needed to spend time there.

“I spent five days at the museums, walked the memorial site late at night, and listened to music performed at Theresienstadt,” Coburn said. “On my final day. I serendipitously met a student group from a school in Prague that was conducting three research projects: one was filming a documentary on the recent discovery of a photo album of real life in Theresienstadt, as opposed to the propaganda by the Nazis about their ‘Jewish settlement,’ Another group was studying tunnel etchings created by prisoners. The third was excavating attics of local homes. I was grateful that they welcomed me to join them. Spending the day with them deepened my understanding of Theresienstadt.”

Coburn said she believes it is an important time in American and world history to talk about the dangers of propaganda and the tools that dictators use to lie, presenting fictions as fact, and fact as fiction, creating narratives intended to divide us.

Being her second novel created, Coburn said these stories are more relevant now than ever before.

“People have not changed. We still have would-be dictators. Dictators who marginalize and hurt disenfranchised communities. But what is more dangerous today is that we have more channels through which to propagate lies, and more ways to hurt one another. I think it is a more dangerous time than the Nazis in the 1930s Germany,” she said.