In astrophotography circles, it’s said it’s mandatory to travel to view a total solar eclipse and to otherwise stay put for a partial one.

Seven years ago, the Great American Eclipse of 2017 thrilled millions with a path of totality running form the coast of Oregon through South Carolina, bisecting the midportion of this country, north to south.

The Great American Eclipse of 2024 cut the country in half again but from a different direction, west to east, starting in Texas and ending in Maine.

The April 8 event had the potential to double the number of eclipse viewers from 2017 with the path of totality passing through several major Eastern Time Zone cities – about 500 towns in all across portions of 13 states and five Canadian provinces.

However, inclement spring weather put a monkey wrench into the festivities with heavy storms in Texas and partly cloudy skies throughout the Midwest and Great Lakes areas until clarity finally presented itself in New England.

EastLake resident and freelance photographer Paul Martinez has now witnessed three total solar eclipses first-hand, starting with the 1991 event from La Paz, Mexico, that lasted nearly seven minutes.

I accompanied him for his second total (and my first) in August 2017 as we ventured north to John Day, Ore., and set up camp on a high school football field to observe (the school rented out spaces as a fundraiser).

That eclipse lasted just more than two minutes. It was over quickly but gave us a taste for the next one seven years in the future.

Initial plans were to observe from Texas for April’s long-anticipated celestial showcase. The path of totality meandered between San Antonio, Austin and Dallas/Ft. Worth, now the country’s largest metroplex encompassing seven million people.

It promised to be a grand show. However, weather predictions were dire for the stretch through Texas with rain and heavy cloud cover expected in the San Antonio region and spreading northward.

The storm did hit the evening of the eclipse and travel conditions were indeed treacherous with golf ball- and even softball-size hail raining down on motorists in the north central region of the Lone Star State.

But, as it turned out, there were breaks in the clouds earlier in the day and eclipse watchers were rewarded with at least a tease. It wasn’t a total wash.

Southern exposure

It was a race against time to find a suitable observing site. We left San Diego at 10:15 a.m. Saturday morning, needing to be somewhere along the eclipse path preferably by Sunday night to stake out a place and set up equipment for Monday’s prize event.

It turned out to be a marathon non-stop 36-hour junket by car, passing through California, Arizona, New Mexico, Texas and Oklahoma to finally reach a suitable destination in Atkins, Ark., a stone’s throw from my father’s birthplace in Russellville and nearby Conway County, the seat of the Brents family in the state.

Paul had put together a series of satellite cloud cover maps prior to departure and it looked like we would find the best observing conditions in southern Illinois, coincidentally the birthplace of my mother in Benton, south of Carbondale, the confluence of both the 2017 and 2024 eclipse paths.

The rest stops along the way, primarily on I-8, were welcome and clean, especially in Arizona. Paul drove through the day and into the night on I-40, eventually crossing into very dark skies in western New Mexico that required a brief stop for some star photos despite howling winds.

By this time, the temperature had dropped to 32 degrees in Grants. We hunkered down in the car for a brief rest while passing through Tumcumcari near the Texas border (which required a more lengthy stop for star-gazing on the return trip).

We passed through the Amarillo region at dawn and quickly found our two-man expedition crossing into Oklahoma. We passing through Oklahoma City with a site, based on updated cloud maps, on north-central Arkansas, which was a straight shot across the state on I-40.

I had not been in this neck of the woods since I was 5 and only have hazy memories of sleeping in a brass bed with lace curtains and weeds growing up to the base of the window. I remember dogs chasing the car on a dirt road when we left the next morning.

That was in the early 1960s.

Fast forward to the 2020s. Everywhere was green with tall, thin trees, ponds and creeks dominating the landscape. This definitely wasn’t Southern California.

The Arkansas River greeted us outside Fort Smith and we stopped at a travel center to get our bearings late afternoon. Southerners, especially Arkansans, are known for their friendliness and hospitality and we encountered nothing less than that while in the Diamond State. It helped, I’m sure, when I mentioned my family was from there.

The Arkansas River took us through Clarksville at the southern border of the Ozarks to Lake Dardanelle, a massive recreation area, outside Russellville, a city of 29,000, where my grandfather studied agriculture following his service in World War I and where he married his first wife, Ethel Smyrna Wright, and had two sons there.

Downtown Russellville had already started to prepare for the impending crowds from all areas (both domestically and internationally) for the next day’s total eclipse. The celebration near the old railway station was tongue-in-cheek and a bit sassy with T-shirts proclaiming, “I Got Mooned.”

The population in that part of the state is fairly homogeneous with ancestry derived from Scotch-Irish, English and German extraction. I may have been born in Chula Vista, but my DNA is very Southern, dating way back to the 1600s in Virginia with the original colonists to Jamestown. I’m very proud of that.

While a podcast from city officials laid out a welcome mat, we quickly found out that everywhere we went was a wrong turn.

“Do you have a reservation?”

“No.”

“We’re full.”

Motels were out of the question at $500 per night asking price. Sleeping in the car another night on the side of the road also wasn’t’ an attractive alternative.

We thought of continuing on to Morrilton, population 6,900, 50 miles northwest of Little Rock, but the motel prices there were only slightly lower at $400 per night. Somebody was obviously making money on this once-in-a -lifetime occurrence.

We appeared out of luck and pulled up in front of a general store in Atkins, population 3,000, midway between Russellville and Morrilton in Pope County. There just had to be something available somewhere.

I googled “tent spaces for rent, eclipse” and the RussellvilleEclipse website pulled up a listing “rentals” that I hadn’t seen before. Miss Josephine’s Ranch was offering $100 a night rentals per plot for tent camping on a 280-acre farm just a few minutes away along Hopewell Road.

I called the number and a voice sounding just like Dolly Parton answered and we were quickly on our way there even though darkness had already set in at 8:30 p.m. local time.

Miss Josephine Stone grew up in nearby Morrilton and was familiar with the Brents family that still lived in the area. That was a definite plus.

Her hospitality was unmatched with her willingness to please her guests.

We drove onto the property, a giant meadow surrounded by trees and a pond, to camp for the night and finally rest our weary bones.

The rural sky was filled with stars from horizon to horizon. This is what my father and grandfather described to me. My grandfather recalled seeing Halley’s Comet filling the sky in 1910.

Paul had bought a tent in Yuma and it proved useful. He set up his camera and telescope tripods and began calibrating with the North Star for the next afternoon’s solar eclipse.

The cameras would automatically follow the sun, snapping photos at predetermined lengths. Altogether we brought 10 cameras for still and video photography.

The night in the tent was chilly with the temperature dipping below 40. We awoke to clear skies but high clouds started to move in about two hours before the main event started.

Oh well, maybe the cirrus clouds would dissipate as the sun moved westward. They did.

The eclipse was midday, starting about 12:30 p.m and ending after 3 p.m. Maximum coverage – about four minutes, 18 seconds — began about 1:50 p.m.

With the sun very high in the sky, one tripod failed under the weight of a 400mm lens and had to be remounted on another tripod, which required a camera to remounted elsewhere. It was hectic getting everything together even though we thought we had made allowances for the worse-case scenarios.

The bottom line is that we needed more help. Each of us needed an assistant to make sure we had checked off all the boxes.

Even though the time duration was double what it was in 2017, the eclipse went by all too fast.

Eclipse glasses we picked up in Russellville’s main street celebration the day before, clearly showed the progression of events, from first contact onward. As more and more of the sun’s disk was gobbled up by the advancing moon, light levels began to drop and, about 10 minutes ahead of totality, crickets began to chirp.

Paul did a countdown and with a few seconds remaining, we removed filters from the cameras and re-set exposure times.

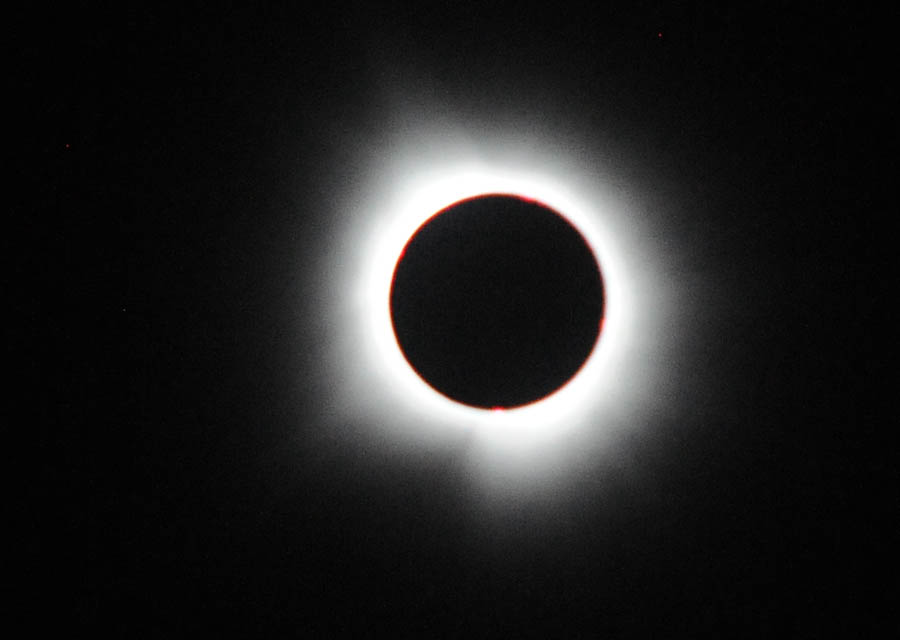

Watching with the unaided eye, the sun suddenly blinked out. The iconic diamond ring – the last rays of sunlight to bend abound moon, was very prominent. When coverage was complete, the solar corona popped out in a majestic display. With the 11-year solar cycle near maximum, the corona was much more extended than in 2017, with several long red prominences plainly visible without magnification.

It was hard to tear one’s eyes away to start taking photos.

It was so utterly spellbinding.

As we learned later, cars had pulled off the road all along I-40 and rounds of cheers could be heard reverberating all around the rural community.

The temperature where we are at dropped about 12 degrees, though we were really too busy to notice. I could see Venus and Jupiter on opposite sides of the blacked-out sun but not the so-called “Devil’s Comet,” 12P/Pons-Brooks, which was much fainter.

Then calamity stuck. I got caught up in excitement of the event and mistakenly switched the main camera from auto to manual, which placed the eclipsed sun slightly out of focus. I had trouble on the back-up camera by putting the ISO at 3200 instead of 320. All the images were overexposed.

While bracketing, I did get a few decent images, however.

Paul, who is a professional photographer, had much better success – just as he did in 2017. His photos speak for themselves.

Glitches aside, it was a worthwhile experience, especially on the return leg to California, despite the lack of sleep and long-distance travel.

Lone Star State

Bonita resident Ron Becijos journeyed to Texas, initially about 100 miles northwest of San Antonio, in hopes of witnessing his second total eclipse after viewing the 2017 Great American Eclipse from Oregon.

The weather obviously proved an obstacle to overcome this time around, but he said he was otherwise pleased with what he was able to acquire.

“On the day of the eclipse, I was dismayed to wake to cloudy skies and no visible sun at 7 a.m.,” the former Hilltop Middle School educator said. “I kept hourly checks of weather for the county I was in and ready to travel to the site with the best weather prediction

“At 10 a.m. I moved from an area near Junction, Texas, where I had slept, 60 miles eastward to Sonora but still within the totality path. It was better there until the eclipse started when larger, thicker rain clouds moved in overhead. Well, it was too late to seek a better spot, so I crossed my fingers and set up my gear. It only got worse.”

Becijos, whose son Ryan ran cross country at Bonita Vista High School and UC San Diego, admitted that through the glitches and poor overcast, there were little triumphs at the end of the event.

“I am happy with that photos that surprisingly worked for me,” he said.

Becijos had brought a 600 mm lens and a tripod for close-ups, plus a wireless shutter release, but experienced mishaps in that department.

Ring of fire

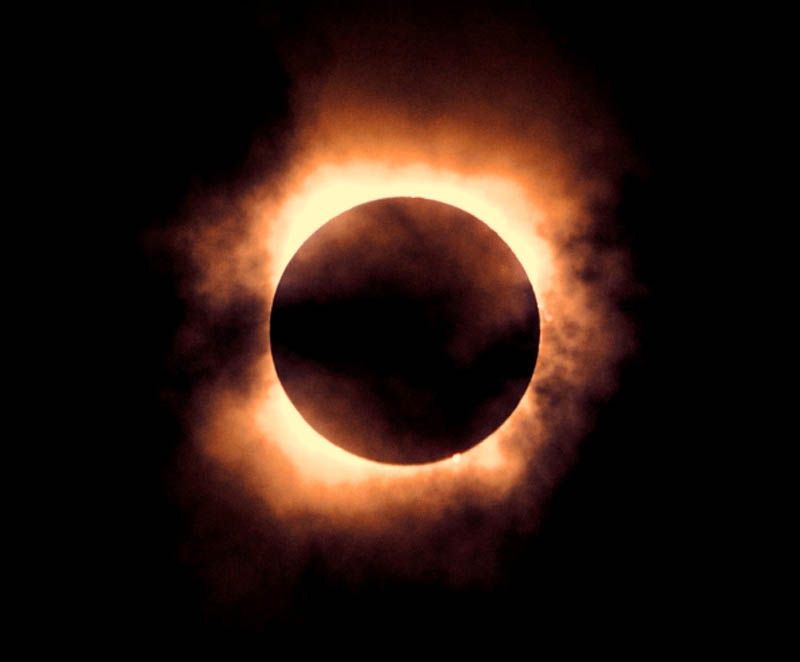

Still, he managed to take several hundred images. Those that stood out from the 2017 event have an ephemeral look due to the cloud cover that adds varying drama and character to each image, he said.

The resulting photos have a distinctly eerie – and decidedly artistic — context.

“There were breaks in the moving clouds, so I pulled off the interstate and travelled on a quiet country road for a few miles where I found a quiet open spot and set up my gear. By that time the eclipse was already starting. Lens filters, polarizers and color gels were at the ready.

“Minutes before totality, I could barely see an image on my LCD screen, so I switched to a polarizer on one of my active cameras.”

Three cameras were used with sun filters and color gels to add interest, with one hand-held f/2.8, 200 mm lens actually capturing a few sun flares. He already has orders for enlargements.

The experience was otherworldly-like, he said.

“At totality, I removed my solar glasses to momentarily view the eclipse with my naked eyes. As in 2017, another mystical experience.

“I was surrounded by the stillness of twilight in the middle of the day. Again, the event felt so intrinsically dreamlike and surreal. What a strange cosmic scene that enveloped my surroundings. The uniqueness in our solar system where sun, moon and earth align to create such a breathtaking event.

“It seems to me that regardless of one’s religion, one cannot help but be in awe of this fantastic celestial happening.

“So, from disappointment to delight, it worked out for me in a nice way,” he summed up. “I feel that both of my eclipse events were amazing and spectacular to witness, and I’m thankful that I was able to capture the fun images of both events.”

Homefront

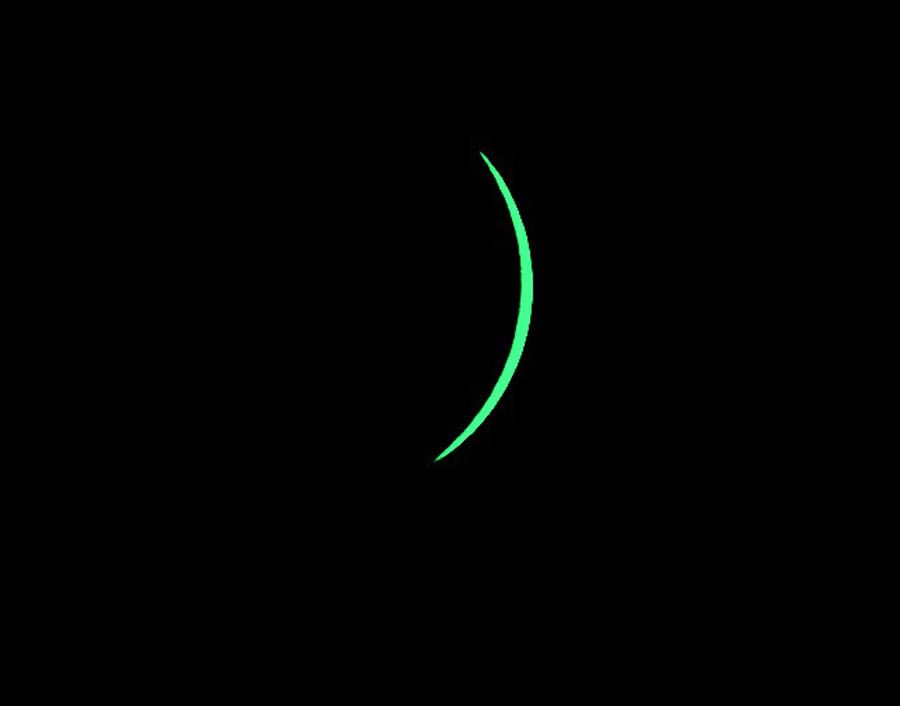

Like a number of people around the county — and the country – EastLake resident Jon Bigornia also wanted to view the eclipse. Locally, only about 65 percent of the sun’s image would be blacked out.

“I knew it wasn’t going to be in totality, but it would be spectacular enough just to witness the event,” he said. “I set up in my driveway, had my chair and glasses on, and preset my camera to capture the different phases of the event. Like clockwork, the eclipse started at 10:03 a.m. local time. At its peak at 11:11 am, not only were the photos showing how much of the sun was blacked out, you could also see that the ambient light had dimmed and the temperature even seemed a little cooler.

“I watched all the way until we came out of the eclipse at 12:23 pm. I also followed the live online coverage of the other areas in the country that had totality, so it was pretty neat to watch that.”

Many other locals gathered at the Reuben H. Fleet Science Center in Balboa Park to partake in the event.

Longtime Paradise Hills resident Lupe Lucero, eclipse glasses in tow, said she enjoyed the public gathering.

“It was a fun event because of all the people there,” she said. “They had a lot of hands-on things for all the kids. KOGO Radio interviewed my grandson.”

Country roads

My trip to Arkansas served as one of self-discovery.

After we had packed up our gear, it was time to visit relatives, albeit them deceased, over the county line. The Brents family has lived in Conway County, Ark., since 1851. My grandfather and his forebearers were born in and round Cleveland, population 76, a small rural hamlet tucked away in a land that time has almost forgot.

In 1900, the town, as it was, resembled the Old West with wooden sidewalks. Horses and buggies were the only means of transportation. It took a day just to get to town to buy the monthly allotment of sugar, coffee and flour.

There was no electricity and indoor plumbing was almost unheard of in the rural outreaches.

My father grew up there before the family moved to Oklahoma to escape the Great Depression but was instead greeted by the Dust Bowl. My grandfather lived in a line shack on his brother’s property with snow covering the floor through cracks in the wall in the winter and sand doing the same in the summer. Six children slept on one mattress, warmed only by a pot belly stove.

My father, who would be 100 if he were alive today, recalled sand covering fence posts. Those were times that are hard for modern day people to comprehend. But my family experienced them and somehow made it through, and became stronger for it.

World War II aircraft factories brought a flood of destitute Arkies and Okies to California in search of work, my family included.

My grandfather liked the climate and stayed after the Germans and Japanese had surrendered.

It was only about 20/25 miles from Atkins to Cleveland but traveling on country roads that took odd turns and were not clearly marked on maps took a while to navigate. We found the Brents cemetery almost by accident just before sundown.

A relative from the past century-and-a-half had deeded the land for a community burial site. Many of my ancestors and their families and neighbors are buried there, including the first Brents to make Conway County home, Joshua W. Brents, and his wife Elizabeth Maxwell .

Joshua was born in 1811 in Middle Tennessee, his wife in 1814 in North Carolina and his mother-in law Nancy Maxwell in 1787 in Ireland.

The small graveyard has stood the test of time — and war. Joshua died in 1863 while his sons were away fighting in the Civil War. With the men folk away, women had to bury him in a goods box.

I found his marker and those of many others whose names I was familiar with from my family research. I was 15 when I sat down with my grandfather to document his knowledge of the family, mainly tales handed down from his grandparents, Wesley Columbus Brents (1847-1920) and Millie Ann Frazier (1850-1933). Wesley came to Arkansas when he was 4, dangling his feet in the mighty Mississippi River while the family crossed in a flatboat.

Millie Ann was born in Mississippi and her father, James Madison Frazier, in Alabama in 1827.

Before Arkansas and Tennessee, the Brents family lived in Kentucky, North Carolina, Virginia and Maryland. The common thread of all the generations was following the western frontier. They lived next to Squire Boone, Daniel Boone’s brother, while in the wilds of North Carolina, and followed the Boones into Kentucky through the Cumberland Gap to live a part of American history.

President Andrew Jackson stayed overnight at the Brents Inn during his re-election campaign in 1832. Several Brents men had served under Jackson in the War of 1812.

The Brentses are a Southern family with many twisting branches. Distant cousins include U.S. statesman Henry Clay, Vice-President John C. Calhoun and Major-General Howell Cobb, co-founder of the Confederate States of America.

Every grave marker told its own story.

There were several that were so weathered that they were smooth and unreadable, God only knowing who was there. Several stones were broken off. In some cases, wooden pegs simply marked the resting place of others.

Infant mortality was high in previous centuries, especially in regions on the edge of civilization. Childbirth, without a practiced physician present, was dangerous and often deadly.

The grave markers acknowledged that.

The names of twins were on one marker. Once Brents child lived only three days before being immortalized in stone.

My grandfather, who I loved dearly, talked about his grandparents often and it was obvious that he loved them. I soon came across their grave markers, side by side, in eternal slumber.

I started to cry.

These were my people.

After 50 years of genealogy research, I had finally found home.

It was a humbling experience.