In Chula Vista and National City, it’s not just people keeping an eye out for crime and suspicious activity — it’s Amazon’s Ring cameras, and they’re always watching. Police are on board and experts and activists are alarmed.

Along with more than 500 other police departments across the nation, National City Police Department and Chula Vista Police Department have partnered or are considering a partnership with the Amazon-owned doorbell security company, Ring.

The CVPD partnership with Ring became active in late July. NCPD is still reviewing the terms of a partnership.

“The benefit to the police department is having the ability for neighbors to share footage of potential criminal activity,” CVPD Capt. Sallee said.

Ring sells video doorbells, security cameras, motion-activated security lighting and security systems. The cameras notify users when there is a motion detected, and allow users to see, hear and talk to visitors in real time, even when they’re not home.

Dave Maass is a senior investigative researcher at the Electronic Frontier Foundation, a non-profit organization that defends civil liberties in the digital world, and a visiting professor of media technology at the University of Nevada, Reno Reynolds School of Journalism.

He said any positive outcomes people are seeing from Ring partnering with police are merely short term and anecdotal, and people should be questioning what the long term consequences will be.

“It used to be people were really skeptical of people looking out the window with binoculars and taking notes on the community. Maybe it’s because it’s creepy to see someone with binoculars but it’s not creepy if it’s invisible,” Maass said.

According to Ring, video footage is only taken when triggered by motion or activated by the user through the Ring app. The Ring app allows users to manage their Ring security devices, but Ring has also created a free social networking app, Neighbors.

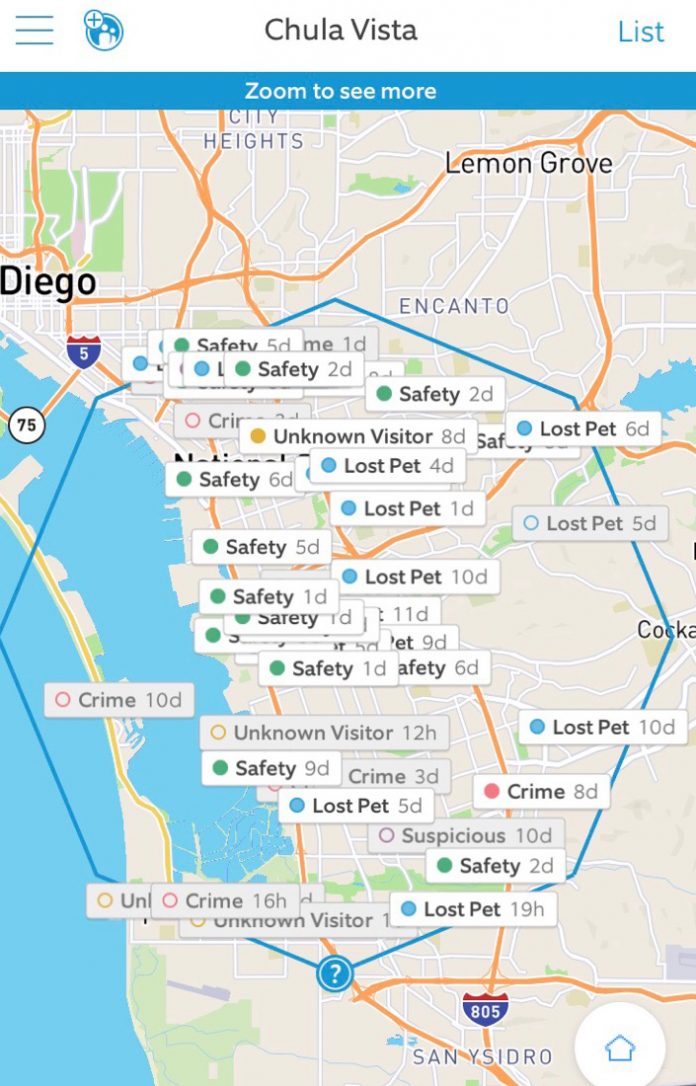

Through Neighbors, people can post footage captured by their Ring cameras anonymously, and comment on other people’s posts anonymously. People categorize their posts so that it is listed in one of five ways: crime, safety, suspicious, unknown visitor or lost pet.

The posts appear on a map for app users to engage with, displaying the date the user made the post and their approximate location for 30 days from the time they’re posted.

When partnering with Ring, officers gain access to a Law Enforcement Portal through the Neighbors app which allows them to notify a particular area of the community where a crime has occurred and request access to security footage captured by Ring cameras.

Officers can also comment on the posts and encourage people to file a police report. Unlike Neighbors users, their comments and posts are not anonymous, their names are listed.

For example, a Ring user posted a video of two men stealing items out of their unlocked truck on Sept. 25.

CVPD CSO Camacho commented “If the vehicle was locked or unlocked it is still a crime to enter a vehicle that is not theirs and take items that don’t belong to them” and then advised them to call the non-emergency police line and file a police report.

“It’s just another extension of police work and the citizen has the option to opt in,” Sallee said, adding that CVPD also makes use of other free social networking sites like Facebook, Twitter and NextDoor.

Anyone with a smartphone can download Neighbors and see posts for up to five miles around their home, regardless of whether or not they are a Ring device owner.

Ring says that it does not view or share user’s videos that are not posted to the app without the user’s permission.

But once Ring users do share content using the Neighbors app, Ring owns the video.

According to their shared content guidelines, users “grant Ring and its licensees an unlimited, irrevocable, fully paid and royalty-free, perpetual, worldwide right to re-use, distribute, store, delete, translate copy, modify, display, sell, create derivative works from and otherwise exploit such Shared Content for any purpose and in any media formats in any media channels without compensation to you.”

Since Amazon bought Ring in May 2018 for more than $800 million, the company has been honing in on police partnerships with the mission of “reducing crime in neighborhoods,” according to their website.

However, in order for their product to be marketable, Maass said Ring must rely on the notion that crime is on the rise in the United States, when it’s not.

According to the Pew Research Center, violent crime in the U.S. has fallen sharply in the last 25 years. Though crime rates differ depending on geographic location, a SANDAG report released in May shows that crime decreased in the City of Chula Vista by six percent from 2017 to 2018.

In contrast, the 2019 CVPD Resident Opinion Survey conducted by SANDAG showed that 42 percent of Chula Vista residents believe that crime has increased and 45 percent of residents believe that crime has stayed about the same.

“I think it’s always in this company’s interest to send the best case scenario to make their product seem miraculous, it’s just this is surveillance product,” Maass said. “They’re never going to tell you what the negative ramifications are.”

He added that law enforcement is not being skeptical enough about this technology, but instead acting to benefit Ring rather than the community.

Ring users in Chula Vista and National City have shared videos on the Neighbors app of people stealing packages and items out of their cars in an effort to find the perpetrators, but they’ve also posted videos where people or children have rang the doorbell and left without incident.

One video posted by a Ring user in Chula Vista on Sept. 27 showed a young boy knocking on the door and looking under the doormat.

The post was categorized as suspicious, and the caption read “Seems to be a kid, but tried to open my door several times, looked under my mat on the front door, then went to my garage and tried to input key code, kept circling left to right.”

The video has been viewed more than 3,500 times. Other Ring users commented, encouraging the person who posted the video to call the police.

Other comments read “Sad because he seems young but on the wrong path” and “Maybe someone was following this kid so he was acting like he lived there or was needing help.” Police have not commented on the post.

Nationally, Ring has been criticized for contributing to racial profiling and increasing people’s suspicion of one another.

When asked about how Ring is working to make sure their users are not racially profiling people of color who come to their door, a Ring spokesperson said every user has to agree to community guidelines before posting on the app which highlight policies against racial profiling.

Their community guidelines read “Never engage in hate speech, racial profiling or other forms of prejudice. Personal attributes like race, ethnicity, nationality, religion, sexual orientation, immigration status, sex, gender, age, disability, socioeconomic and veteran status, should never be factors when posting about an unknown person.”

But just because these guidelines are in place doesn’t mean racial profiling is not happening via Neighbors.

Last Halloween, The Washington Post brought a video posted on the Neighbors app in a Maryland neighborhood to Ring’s attention. The video showed a video of two boys ringing their doorbell with the caption “Early trick or treat, or are they up to no good?”

The video racked up more than 5,500 views, and led to an influx of comments questioning the boys’ motives, when all they did was ring the doorbell on Halloween, according to The Post. It was only removed by Ring when The Post brought it to Ring’s attention.

“The majority of posts to Neighbors meet our guidelines and those that do not are removed by the Ring team. We also encourage Neighbors users to flag content they find to be in violation of our guidelines,” a Ring spokesperson said in an email to The Star News.

Maass said that through Neighbors, you can see some of the worst inclinations of your community brought to life, and Ring is encouraging people to “blow the whistle and pull the alarm string” when is comes to exposing someone they perceive as suspicious.

“I think in particular, in the communities you’re talking about, the people that are more interested in installing are often wealthier people, people who have disposable income and that’s often going to be a white population,” Maass said.

On Tuesday more than 30 organizations, including RAICES and the National Immigration Law Center, echoed these concerns. For the first time, a joint letter was published online calling for elected officials and specifically Congress to put a stop to the partnerships.

“These partnerships pose a serious threat to civil rights and liberties, especially for black and brown communities already targeted and surveilled by law enforcement,” the letter reads.

The letter also addresses reports by The Intercept and The Information that Ring allowed employees to share unencrypted customer videos with each other. Ring denies these reports.

“The Ring technology gives Amazon employees and contractors in the US and Ukraine direct access to customers’ live camera feeds, a literal eye inside their homes and areas surrounding their homes. These live feeds provide surveillance on millions of American families—from a baby in their crib to someone walking their dog to a neighbor playing with young children in their yard—and other bystanders that don’t know they are being filmed and haven’t given their consent,” the letter reads.

Ring doorbell video cameras start at $99. In order to save and share video footage, Ring device owners have to buy a protection plan, which starts at $30 a year or $3 a month.

Only the Protect Plus Plan, which costs $100 annually, provides users with “Ring Alarm professional monitoring.”

This means that when the alarm is triggered, Ring officials contact the user. If Ring officials don’t hear back from the first point of contact listed for the account or the second point of contact, then they call the police.

Emails acquired by The Star News show that Ring gave NCPD officers a discount on Ring products, and gave CVPD free products to give away at National Night Out. Both CVPD and NCPD advertised Ring products at National Night Out.

Maass said the relationship between law enforcement and Ring is something to be skeptical about.

When asked about whether a partnership with Ring could create a disparity of communication with police between people who can afford Ring security and people who can’t, Sallee said he could see that argument if it was the only way police are handling outreach, but it’s not.

Ring would not disclose the number of Neighbors app users or Ring device owners in Chula Vista or National City, per their company policy.

Maass said he’s concerned with these devices being hacked, who could potentially get a hold of the information and the dangerous repercussions of an abusive partner gaining access to Ring cameras in domestic violence situations.

“It can be fairly easy to compromise someone’s account,” Maass said. “Lots of things are being compromised all the time.”

Two patents filed in November 2018 suggest that Ring wants to expand the kind of data it collects using facial recognition technology. A Ring spokesperson said the company does not currently use facial recognition technology.

Facial recognition presents another array of potential problems — 2018 studies by MIT and the ACLU have shown it’s significantly less accurate in identifying people of color and women.

“Somebody is convincing them to spend their money to sell their own privacy away. They should think twice about that, they should not be so complicit in building the surveillance state,” Maass said.