Little about the southwest corner of Bonita Road and I-805 seems special today. Preoccupied motorists roar past a chain hotel and a busy Denny’s that lure travelers heading to or from Mexico with affordable rooms and Grand Slam breakfasts.

Too bad. It remains sacred ground to a generation of former South Bay baseball players. Mr. Ortner’s house used to be there.

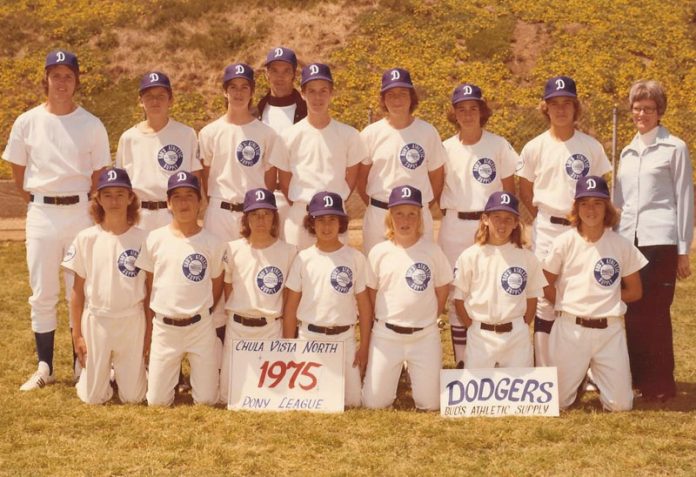

During Aprils past, in a creaky ivory cottage, lived the septuagenarian sage, wise as Stengel and kind as a warm spring morning. Teenagers in the Age of Nixon dreaming of chysalizing into the next Willie Mays, Henry Aaron or Roberto Clemente would make the short pilgrimage to his cottage, bats on shoulders and cleats laced tight.

Richard Ortner was born to be a baseball coach, though he’d have pulled my Sweetwater Valley Little League cap over my eyes if I’d ever said that to him. He had planned to be a big league baseball star himself. He was on his way, he reminded us many times. The Chicago White Sox had signed him as a catcher out of high school and he could hit the ball out of any minor league stadium in America.

If only it wasn’t for the accident, he’d say. An off-season mishap in a Midwestern sawmill severed a once-promising career by shearing three fingers off his left hand. Unable to grip the bat tightly, he could no longer hit the ball out of any minor league stadium in America. He could barely hit the ball at all.

His baseball career in ashes, he joined the Navy during World War II and tried to build a new life. Instead, life wound up and threw him a high hard one for strike two. A boiler he was tending on a destroyer blew up and permanently damaged his hearing. By the time he was teaching sweaty Bonita kids to throw a curveball in the 1970s he was almost completely deaf.

Teenage boys can be cruel to a weathered man with seven fingers and bulbous hearing aids, but we all loved the skinny ol’ guy in the faded New York Yankees cap who could still send the best of us flailing at overhand sinkers in the dirt.

Mr. Ortner took a special liking to me and a friend named Tony Camara, and became our private baseball guru. Tony was well over six feet tall and strong as an ox. I was a lanky 5’ 7” outfielder who was strong when I didn’t wash my baseball jersey.

Like a sundown ritual Mr. Ortner would pitch batting practice to us until we could finally line that pesky outside curve to right field. He would hit us grounders and flies until it was too dark to see them in the balmy spring evenings.

After our workouts he would pull me aside and say, “Max, you’ve got what it takes to be a Big Leaguer. You can hit, you can throw and you’re fast.” Then he’d shake his head ruefully and add “Tony’s a helluva a nice kid, but I think he’s gonna have problems ever getting anywhere as a ballplayer. He’s too clumsy and slow. Poor kid.”

Poor Tony outgrew his gangliness and became one of the finest athletes Bonita Vista High School has ever seen. Besides making first-team All-CIF in basketball, Camara was first-team All-CIF in baseball and was one of the most feared prep hitters in America. His homeruns are still remembered with reverence.

He accepted a scholarship to national powerhouse San Diego State and made his debut by hitting a walk-off tape-measure grand slam in pea soup fog against UCLA in the bottom of the 10th inning to win the season opener. He was first team All-American as a senior and drafted by the Detroit Tigers.

“Can’t miss Max” missed, closing out his career as a singles hitting outfielder for a backwater Washington State college that won 5 and lost 34.

Mr. Ortner just shrugged it off as Camara went to the Tigers and I went to graduate school.

“Nature just plays these tricks on people,” he would say. “Too bad you didn’t fill out like Tony.”

One April afternoon in the Age of Reagan, while we were sipping pink lemonade in faded baseball trading cups and discussing the literary merits of Roger Kahn’s baseball epic, “The Boys of Summer,” a delivery man began to fill the living room of the decaying white house on Bonita Road with state-of-the-art stereo components. His wife told me that despite their very modest means she had ordered the pricy equipment, along with dozens of recordings of the world’s greatest music by Chopin and Mozart, Louis Armstrong and Frank Sinatra, The Beatles and Elton John.

“Dick will be completely deaf soon,” Mrs. Ortner told me. “I want him to hear all this great music while he still can.”

Richard Ortner died soon after, but not before he could whistle the Ode to Joy from Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony. Learning the Ode was not hard for him. It was springtime and baseball season had arrived.

Max Branscomb is Professor of Journalism at Southwestern College and faculty advisor of the Southwestern College Sun student newspaper.